The Degrees of the Station of No-Station

Regarding the End of the Journey

Omar Benaïssa

Articles by Omar Benaïssa

“Say: Lord, increase me in knowledge” (Qur’an,XX:114)

“Those who believe have a stronger love for God” (Qur’an, II:165)

The notion of station (maqām) in Sufism ought not to be very difficult to understand. We know what a position, a grade, a rank and an office are within a political, military or administrative hierarchy. We are also familiar with the different stages of education which, through a series of examinations and tests, lead to a diploma. There is a recognised difference, however: if Sufism is also regarded as an education – for the relationship is that of master and pupil – then its school, although open to all men and women, only comprises those students who continually seek more (murīd), who agree to submit to the spiritual authority of their master, and to obey him, for it is a question of replicating a relationship that originated with the prophets, and the saints who teach by example.

It should not therefore be difficult to imagine what a spiritual station is, and to what it can be compared. Even if modern psychology does not know what a spiritual station is, it knows about psychological states (emotions, joy, feeling depressed, feeling desperate, seeing the light at the end of the tunnel) and psychological types which, even if they cannot be compared to these stations, can serve to illustrate them.

The expression maqām (spiritual station) is part of the technical vocabulary of Sufi literature. It does not refer to an office in the initiatory hierarchy but to a degree, or rank. This means that a person can have attained this station without necessarily being invested with any active power or authority.

But in our attempt to understand the notion of station, it must be said straightaway that any description of it, or any definition that could be given of it in an objective fashion, that is to say by drawing on the Sufi texts, could never be wholly adequate. These writings are often themselves descriptive, analytical and impersonal, revealing the internal structure of Sufism, but never disclosing how this psychological evolution takes place at an individual level in relation to a particular disciple, how little by little this disciple will learn to react in a different way, and follow a path that will lead him far beyond the ordinary perception of the world. That is something that is the province of autobiographical account. But such accounts are quite rare among Sufis, who are very reticent, particularly since each experience is in many respects personal, incommunicable and unique.

The stations, and especially the station of no-station (maqām Id maqām), pertain to spiritual experience. As a notion, the station of no-station appears very frequently in the writings of the masters under different names (mawqifmā warā al-mawāqif, maqām al-maqāmāt, maqām al-tawhīd, maqām al-qurba, etc.). But as an expression, it appears very rarely. Ibn ‘Arabī used it in the Futūhāt al-Makkiyya[2] in a technical sense, crediting Abū Yazīd al-Bastāmī and others with having attained it, as though he wanted to suggest the rarity and also the measure of it. In the Jawāb al-mustaqīm,[3] to the brief list of those who have known this station (which he calls here the station of Virtue, maqām al-ihsān), he adds Sahl ibn ‘Abd Allah al-Tustarī, who is his favourite, and with whom he links himself in a poem in one of the chapters of the Fusūs al-Hikam.[4] Since Ibn ‘Arabī only allowed himself to speak about what he knew from experience, it must be assumed that he himself had also known the station of no-station. The numerous expressions employed to describe a final station certainly convey many subtle, and difficult to grasp, differences in meaning. They also suggest the unique and personal character of each experience.

For Ibn ‘Arabī, the idea of personal experience nevertheless fits into the categorisation that he established in the Fusūs al-Hikam. On the one hand, the viator, or traveller, puts in the effort, while on the other hand it is God who creates the path that the viator will take. He will be in “the footsteps” (‘alā qadam) of this or that prophet. The paths are already marked out.

There is also the sense that a mystical journey which does not end in no-station is very much a journey that is incomplete, which raises the question of the destiny of the soul that does not become perfect, or close to perfection. Each and every one of our efforts to reach other new stations are repeated attempts to break out of the strait jacket that keeps us in this world and prevents us from being born in the other world.

Every rank attained which does not open directly into no-station is but a false door. This is why Bayāzid said: “Each time I thought I had reached the end of the Way, I was told that this was the beginning of it.”[5] Only one door will open onto the divine void, the divine Ocean, and it is this door that the viator searches for. Sometimes he has to take the longest way round, trying all the doors and only coming across the right one last of all. Others are lucky enough to see it opening at the first attempt.

The Way is also a relentless struggle for survival. The station of no-station practises natural selection; only those who reach it survive. Sufis are the Darwinians of metaphysics.

Since this does not apply to us, we can only talk about it by reference to a mental representation based upon the written teachings of Sufism. To make such a representation for ourselves, a broad knowledge of Sufism is therefore necessary. For this reason, it is necessary to distinguish, on the one hand, between the logical degrees and on the other the degrees that are expounded in well-known Sufi texts, such as Ansāri’s Manāzil al-sā’irīn or the Mawāqif of al-Niffarī (d. ca 354 ah)[6] or the chapters of the Futūhāt al-Makkiyya by Ibn ‘Arabī, which are psychological and metaphysical degrees, that is to say psychological states and pitfalls that the disciple encounters, as well as the metaphysical knowledge that is revealed to him as he advances through the different stages. In Sufi writing, these degrees are presented in a structured way, categorised, and ordered in a didactic fashion.

From a logical perspective, an uninitiated reader would have difficulty in understanding for example what lies behind the sudden shifts in meaning that occur in the works of al-Ansārī and similar authors, or again how a verse of the Qur’an is suddenly given an unexpected interpretation in a context which the reader not used to the allusive style of the Sufi masters would not be able to understand a priori, or perhaps even accept. In his letter to Kāshānī, Semnānī writes: “What does logic matter, once the objective has been achieved?”[7]

Logical Degrees

(1) We have here an expression that a priori does not make sense according to formal logic. How can that which is not a station be called a station? Surely this is a contradiction of the principle of non-contradiction (A is A, A is not not-A), a paradoxical statement?

Or is it simply that it was defined in the negative as a way of giving a provisional name to something that follows on from a state of affairs in which the stations succeed each other in a normal manner until there appears a state of affairs which seems to be unlike anything that has come before? A simple matter of denomination, or is the substance itself anti-station? Should lā maqām therefore be translated as anti-station, that against which the stations lean and rest, in the sense of an opposite (anti-matter) or in the geographical sense (anticline, anti-atlas)?

(2) If the station of no-station means the moment when one has not yet attained any degree or any merit, it would then be the zero degree before the first maqām.

(3) In circular representations of the initiatic way, this station would be the one where the two extremes meet, where the serpent bites its own tail.

(4) Should the station of no-station be taken to mean a station beyond which there is no other station? By implication this would be in Arabic maqām lā maqāma ba’dahu (a station beyond which there is no other station). It would therefore be the absolute station.

In other words, the station of no-station would be the terminus, a central station at which all the trains coming from all the stations would arrive. It would be a kind of metropolis, the sole and final destination for all the trains.

(5) Or else, is it another station, called no-station, which is not to be confused with the last of the stations as described in the Manāzil al-sā’irīn? It would thus be a station only in name. If this station called no-station is not to be confused with the last of the stations, then presumably it can be reached by different routes from those of the one hundred waystations, since it is not connected to them. It could suddenly sweep over us at any moment, since clearly it is not governed by the same rules that mark out the “tourist route” of the mystical journey (siyāha).[8] The station of no-station would be a station situated outside the circuit (represented by a circle on which there are points marking the stations). Each station would thus have its parallel, invisible, station, in which the traveller could unwittingly find himself, and which would be the station of no-station (represented by two concentric circles).

“Go to and fro freely in the world… “[9]

But on this “trip” towards God, you are advised not to allow yourself to be captivated by the beauty of the landscape. You must constantly remember that beauty is unique, and that it is the beauty of God. If you gaze upon something of exceptional beauty without returning it to God, you are wasting your time!

Ey dūst shekar khoshtar yā anke shekar sāzad

My friend, is it the sugar that is sweeter or he who makes the sugar?[10] (Rūmī)

Can every station give access to the no-station? Or is it necessary to travel through all the stations in order to be able to reach the station of no-station, even if the latter is not locatable in space?

(6) If every station gives access to the station of no-station, does this mean that these stations of no-station are necessarily relative, and that the station of no-station arrived at after having passed through all the requisite stages is the only true one?

(7) There is another possible meaning: station (in the next world) and non-station (in this world). It is a station, but it is no longer categorised as a station of this world. It is the first station of the next world, perhaps the one where the initiate enters the imagi- nal world (‘ālam al-mithāl) or even the one where he begins his journey in the Essence. For some texts imply that the station of no-station is situated rather in an epiphany of the Divine Essence, and thus beyond the imaginal world. It would therefore be the station of “perhaps even closer still… ” (aw adnā),[11] the one that is beyond the epiphany of the Names, where Gabriel risked burning his wings if he ventured there.

(8) Every station is called no-station until a new, undreamt-of station looms ahead, like a new peak suddenly rising up in front of the mountaineer who thought his troubles were over. The station of no-station thus signifies the station that is pending, provisional, transitional.

(9) A station is called a station because one can discern one’s position there: there is an above and a below. The height is evidence of the station. It is said of a king that he occupies the highest rank (maqām), because he also occupies the highest part of the throne or tribune.

The station of no-station would thus be the station where one no longer perceives that which is lower as such, where everything is levelled by reference to what is higher, and where it is revealed to us that all the stations are perfect at whatever degree they might be situated. The degrees disappear. The miracle is to see that God is to be found in His totality at all the degrees, at all the stations where He manifests, in all the degrees of manifestation, from the most radiant to the most obscure. “And the earth shall shine with the light of its Lord… “[12]

All of these questions are of a logical order; they are all tenable in reality.

Literature And Art

Fiction and literary narratives in general provide us likewise with similar examples and descriptions of these states because their heroes are not described abstractly, with a view to illustrating a thesis. They live like real characters in everyday life, encountering experiences that can be likened to those that spiritual disciples go through. Writers of fiction depict their heroes as passing through and being transformed by a series of condensed stages on their journey through the pages of the book, and as living a “Romantic” life, a life full of adventures. These heroes experience despair, they eventually see the light at the end of the tunnel, they come out into the light, they attain their goal, they experience pain and joy, and they mature. Many of these accounts can be regarded as descriptions of quasi-stations, which can be compared to spiritual experience.

The station of no-station can be glimpsed in blazes, or flashes, like being able to witness heroic exploits through a pane of glass, without oneself having the necessary qualifications for taking part in the action. Or, as if on a TV screen, we are able to watch scenes unfolding far away from where we ourselves are. The images convey emotions to us which involve us in the ordeals of the heroes.

In dreams, this state presents itself to us in the form of premonitory images of what the future holds for us. In Sufism, there is always anticipation: what one sees at the beginning is what will be realised in the future. These visions prepare the traveller for what will later become, if he reaches it, his final station.

The artist passes through periods, phases in the evolution of his art, during which his art acquires gradually more and more maturity, more and more precision. He tends towards absolute art. Thus, as Coomaraswamy[13] would say, the best artist is the one who could represent a landscape, a still life, a portrait, such as it would be in the mind of God, as it is in God. Such is the artist who practises painting beyond painting, which seeks and perceives a form beyond form and colour.

From this point of view, Sufism is an art. It is what explains why almost all Sufi masters are poets. They have acquired the art of concise expression, the art of speaking like God, inspired to say things aesthetically and in truth. This is why many Sufis are good calligraphers, poets, etc.

The Station Of No-Station In History

History and legend also reserve a special degree for certain individuals, who become timeless and never leave the stage of sacred or mythical history, hundreds or even thousands of years after their death. This is true of the prophets, characters from the Bible and legend and characters from Greco-Roman mythology (The Argonauts), or from Indian mythology, etc.

They are “undeposable”: they are thus in the degree of no-station. Only he who is in a station can lose it. The wave of the history of time only carries away in its flow those who stand in its path.

A station is restrictive. It imposes constraints on the one in whose care it is and requires him to obey certain rules, failing which he will fall and lose the quality of it. As with every quality, honorary or real, it is subject to etiquette. Noblesse oblige.

The station of no-station would thus be something that would apply to a “liberated” being, free from constraints – such as the malāmatiyya, the heroes of Greek mythology, Jason and the Argonauts, Ulysses, Hercules, and other demi-gods. In Persian, they are called “kings” (Shāh), Shāh Ni’matollāh Valī, Safī ‘Alī-Shāh, etc. perhaps because they have arrived at the Divine Throne (‘Arsh).

Switching into symbolic mode, the epics of Homer or Virgil can be regarded as a record of the great events that lead exceptional men to a station of no-station, since they make their heroes go through adventures and trials that make them worthy of attaining their goal, and this takes place beneath the beneficent gaze of the gods.

This applies also to Ferdowsi’s Iranian epic Shāh-nāmeh (The Book of the Kings), and other mythical epics of an initiatic nature.

We could paraphrase Paul Valéry and assert that all literature implies (and is generally unaware that it implies) a certain idea of man, and even a view on the destiny of the species, a whole metaphysic that ranges from the rawest sensualism to the boldest mysticism.[14]

Formally everything is maqām; the whole of life presents only maqāms. It is by virtue of their content that the stations differ from one another, and that the initiatic maqām is higher. Otherwise, a man who had succeeded in making his fortune by becoming a multimillionaire, or a man who had won the heart of the most beautiful woman in his village, or a man who had succeeded in getting elected mayor of his town – all would have reasons to think that they had attained a high maqām, as a reward for their efforts. This formal resemblance is, moreover, the foundation of Sufi parables and metaphors: the higher is explained by reference to the lower, which is an image of it.

Everyone is on the Way. But not everyone is aware of it.

Each one of us is able to turn back towards our past and measure not only the progress we have made in life, the obstacles that we have overcome (that which does not kill you, makes you stronger), and the degree of maturity gained; but also the flaws that are innate in us, the transgressions for which we cannot forgive ourselves… ..

Man is thus on a path, although he does not know it, even if he comes to realise that his life has not been merely an adding up of minutes, or the passing of time.

The station of no-station would therefore have as its first meaning the place where one does not yet know what a station is, where one does not yet have any station. When that is realised at the end of the mystical journey, one discovers that what was true at the beginning of the journey is confirmed at the end. But this confirmation is a reward: the person learns that in fact he or she has no maqām.

The conscious entry into the Way thus marks the beginning of the path. It is the moment when the path makes its appearance, as an indistinct, hazy form emerging beneath our feet. It is the Way that comes to us, like a path that we were following without knowing it, covered in dust that the wind of Providence comes and sweeps before us.

In practice, this entry begins through meeting with a master, through being fascinated by beauty, by love.

Che daārad dar del ān khwāje Ke mītābad ze rokhsārash

What does that gentleman have in his heart That is shining in his face? (Rūmī)

Spiritual masters are able to discern those who have the potential for following the way of light, those who are ready for service. For,

Dar rah-e manzel-e leylī ke khatarhāst dar ān Shart-e avval qadam ān ast ke majnūn bāshī

Many are the dangers along the path that leads to the dwelling of Leylī

The condition for taking the first step along it is that you have to be mad.[15] (Hāfiz)

But the advantage of the Way is that it teaches shortcuts, it enables you to save time, and to discern more quickly any technical difficulty that will hold you up.

This entry into the Way, the first step, the first condition of which we have just seen in a verse by Hāfiz, comes down to pure, genuine love – for the state of Majnūn means nothing other here than an attitude that challenges any faith in the rational mind and in the selfish motives of passion.

Hīlat rahā kon asheqā! Dīvāne sho dīvāne sho!

Lovers, abandon guile, be crazy, be crazy! (Rūmī)

The entry into the Way could justify an entire symposium devoted to it. All the stations that are passed through will only deepen this first perception of a hidden world, of the conviction that it is worth exploring. He who has tasted the sweetness of something can no longer contain himself!

In this connection, there is a story about a sheikh of the ‘alawiyya tariqa, the Sheikh al-Madanī, who approached a group of young thieves.[16] He offers them some easy but well-paid work. They agree to follow him. When they arrive at his house, the ‘alawī sheikh arranges them in a circle and asks them to recite zikr for one hour. When they have finished, he pays them a sum of money with which they are more than satisfied. Naturally, they ask for more. They come back the following day. At the end of a few days, the louts become the murīds of the sheikh, and decide to enter the Way. The ‘alawī master had discerned in them the inclination towards spiritual matters. All they needed was a taste of the pleasure of zikr to be convinced.

It is possible therefore to have done the mystical journey, to be so far advanced, to have got so close to the goal, without even realising it. A single spark, or a nudge, would be enough to become fully realised.[17] Everybody knows the story of the brigands who were the first disciples of ‘Abdulqādir al-Gilānī.[18]

There is such a truth in this that for many the beginning is often confused with the end of the mystical journey. They reach the goal the same day that they become aware of the path. Others with less inclination will not take another step, for the first taste is enough for them. They have achieved their measure, their relative perfection. They did not need to drain the cup to its dregs; sniffing the cork was enough to make them inebriated.

But then there is a rule which I shall explain through the Algerian proverb: ellī sabqak b’lila, sabqak bi-hīla: he who is born one night before you is one trick ahead of you. It applies also in Sufism. Besides, it is surely of Sufi origin: he who is one night ahead of you on the Way, is one (Sufi) trick ahead of you.

In order to be a master – that is to have the ability to guide another person – it is necessary to be at least one stage ahead. For one can only lead and guide toward what one knows. Hence the necessity for an initiatic chain.

But perfect masters treat their disciples, and others in general, as though they were already what they have been called upon to become, precisely in order to help them to become what they are capable of becoming. The most accomplished master can only lead you to your own perfection, for perfection is relative.

Metaphysical Degrees

Some preliminary comments on the theory of knowledge in Sufism:

Intellectual Sufism, particularly with Ibn ‘Arabī, effected a definitive break with the deus ex machina. There is no god but Allah. This is interpreted as an immanent function in the world, which is inseparable from the Creator because, quite simply, the creation is a mirror of God, a constant divine effusion. There is no discontinuity, no gap between God, the Uncreated, and the created world.

In place of a theology in which the Divine Essence is contemplated from a theoretical point of view and where care is taken to rid it of everything that would be contrary to its perfection, which is the essential precept, we have a theosophy or rather a practical discipline that makes Man the central focus of knowledge rather than God. It is in Man that knowledge occurs and it is Man who must be rid of his imperfections in order to gain awareness of this active presence in the world that we call God. It is therefore a matter that is entirely the domain of Man. To know God is to realise that the world is His manifestation; it is to realise oneself, to realise what it is to be a human being.

The goal of Sufism is real knowledge, not theoretical knowledge.

There is no God apart from the Manifestation; there is no access to the Essence (because it is unknowable and that is all that is known). Man in his turn realises that his essence does not exist except as something provisional, with the potential to become a cosmic function; he is the province of knowledge, the medium for the Divine Names. The created beings (al-insān al-makhlūq)[19] are animals, as Aristotle says, and endorsed by Ibn ‘Arabī, for whom Man denotes first of all Perfect Man. When the divine form leaves the human body, then shall the trumpet sound heralding the end of the world.

We do not know God; we know al-ulūha, the divine function, in so far as it is manifest. We pass through the various levels or planes of the divine manifestation (Acts, Names, Essence). At each level, we transmute, we shed a skin. There is a constant relationship between us and the way in which we array ourselves in the Divine Names and Attributes. Man ‘arafa nafsahu fa qad ‘arafa rabbahu… ..

If the Torah is written on the “skin” of God, as the Kabbalists allege, then God sheds a “skin” each time our level of understanding of the Torah changes, for it is in the “skin” of God that we are reading.

There are three moments in Sufi metaphysics:

precreation | creation | de-creation

In concrete terms, these three moments correspond (1) to the moment when God wanted, desired to be known, or lover (muhibb), (2) to the creation or manifestation or hubb, love, and (3) to the return, or beloved (mahbūb).

Lover | Love | Beloved

One can continue in this fashion with triads such as ‘ārif, ma’rifa, ma’rūf / murīd, iradat, murād, etc.

At each of these moments the immutable essence (‘ayn thābita) follows God and obeys Him. As God desired it, it too loves to be known; it contemplates the beauty of creation when it is itself brought into existence, and it finds itself the object of the love and attention of God, when it returns to the Essence. God loves it with the same love that He feels towards Himself. It becomes a murād.

The ascent to the station of no-station is nothing other than an attempt at bringing together, jam‘, and then the unification of the metaphysical principle. The mystical journey is in God.

Finally, the station of no-station is a way of going beyond the contradiction of the opposites.

Instead of giving it a specific name, Ibn ‘Arabī has kept the expression maqām lā-maqām as a whole because it conveys this special state of the junction of two worlds. It is a station on the human side, and a non-station on the divine side. The station belongs to Man and the relative indetermination of no-station belongs to Him. It is an expression that makes allowances: to the created, that which is his due; to the Uncreated, Its language.

Immanence on the human side, and transcendence on the divine side.

It is the station of no-station because it is a station in which one cannot remain, an untenable station, that has to be quickly relinquished, for it would be a conceit to aspire to stay there. The sālik must retrace his steps, for he is reminded that he is but an empty shell, an impotent creature. The maqām is an illusion for Man. The maqām is God’s alone. The sālik understands that he is a cosmic and ontological function, predetermined in his attributes since the beginning of time. The sole purpose of the mystical ascent was to reveal this to him. Moses has been Moses since the beginning of time and Muhammad has been Muhammad since the beginning of time. The people of the lā-maqām are pure servants (‘abd mahz). Thus the station of no-station seems to be the boundary where Man reaches the borders of the divinity, and where he must necessarily realise and affirm his essential servanthood (‘ubūda).

This should be related to the famous Qur’anic verse VIII: 17 (“It was not you who threw when you threw: it was God who threw”) and to what Khidr reveals to Moses: “In all of that I did not act on my own initiative” (Qur’an, XVIII: 82).

A station is something of which one becomes aware, but to become aware of a station is to go beyond it. This is explained by the fact that knowledge is dependent upon the station, and the station always corresponds to a level of knowledge. We are what we know. To be is to know. Intensification of the act of being depends on intensification of knowledge and vice versa. But the Qur’an, which links the two (knowledge and station), in its promise, seems to accord ontological primacy and the motive role to the pursuit of knowledge. The Prophet was ordered to ask for an increase in knowledge – “Say: Lord increase me in knowledge”[20] – and God promises him an increase in station: “It may be that your Lord will exalt you to a praiseworthy station (maqām)”.[21] It is knowledge that must be sought, not the station. It is God who bestows the station as a reward for the degree of knowledge. But here station has an honorary meaning (makāna).

Mysticism implies the search for a secret. Sufism teaches that the secret is not something external, like that sought by MI6 or the CIA. It is not outside us. It is not something other than us. We are the secret. This implies that the world of ordinary everyday appearance conceals something that transcends it, but which enhances its value and refines it. The Sufi quest is not an asceticism that consists in casting off the world. It consists in wearing the world inside out, or rather turning it the right way round. The veil that presents the world as something essentially negative must be lifted so that the light that it hides can be contemplated. Thus the Sufi is not a destroyer of the world. Quite the opposite. He is not an ascetic. He is a man who seeks happiness, Life. He endows the world with life and with light. He renders the world to God, in accordance with the shat-h of Jesus: “render unto God that which belongs to God and to Caesar that which is Caesar’s” (Matthew). When everything that belongs to God has been rendered unto Him, where then will Caesar be, what will remain of Caesar?

The world has a Sufi future. When the world is finally perceived in its reality as a manifestation of God, the Sufi will be revealed as one of the cogs in this wonderful divine machine. Thus his aim is to preserve the world. He participates in the perpetual creation of the world. This is what the station of no-station is.

This is evidenced again in Islamic mysticism, when compared with Plotinian mysticism for example, by the fact that it considers that the world and its source, the soul and the body, are not completely separate in a Manichaean manner, the one being good and the other evil. There is always an intermediate world, not only at the macrocosmic level but also at the level of the smallest particle, an intermediate level where the two aspects touch each other and constitute an indissociable and indivisible unity. An ignorance of the imaginal world is what transformed all the earlier schools of mysticism into ascetic systems, aimed at freeing the soul from the body.

There are several forms of ascent that are differentiated from each other according to the method followed. Each one ends in a kind of knowledge. In this connection, you may like to read the excellent contribution to a recent conference in Rabat by my friend Stephen Hirtenstein on Ibn ‘Arabī’s Brotherhood of Milk.[22]

Images Of The Real

Sufism teaches through anecdote, metaphor and image. Let us look at some illustrations of this point:

Image A: An alif with an infinity sign modified by plus or minus signs (+ or -) at each end. This alif is the Way. When it reveals itself it contains in reality the Tree of Being. Alef-e qāmat-e dūst (the alif which is the shape of the Beloved)! It is the alif that it would be more accurate to depict in a horizontal position, like the bā’.

In any event this alif, which extends from pre-eternity to post-eternity, is the location of the mystical journey. At which station does one reach it? God alone knows.

Hāfiz said:

Az azal tā be abad forsat-e darvīshān ast

The time of the dervishes stretches from pre-eternity to post-eternity.

In theory it can be reached at any moment. The letter alif is thus the only letter that exists. All the other letters are contained in it. Hāfiz has also said:

Nist bar lowh-e delam joz alef-e qāmat-e dūst

Che konam harf-e degar yād na-dād ostādam

There is no other letter on the tablet of my heart, except the alif, the shape of the Beloved

What is to be done? The master has not taught me any other letter except that one!

Image B: Since the location of the mystical journey is a long path, let us content ourselves with examining an enlargement of a segment of the Tree of Being magnified a billion times through a metaphysical microscope.

We see a vertical segment indented alternately on either side (like an ear of wheat, or the Tree that it was forbidden to touch for it causes vertigo, or like DNA). This is the “distance” covered in a lifetime by a sālik who has attained the maqām lā-maqām. The alif is serrated on all sides because the chance to climb it is offered to everyone, and via every route. In fact, there is only one path for each person, and no path encroaches on another.

“If the ephemeral were compared to the Eternal… “

Image C: This is the technical aspect of the passage from one station to another, represented by a spring, which signifies that once a station has been traversed, it already affords a view of the next station, and is preparing one for it. But for a moment, this station is taken for the final station, as we have seen in the quotation from Abū Yazid al-Bistāmī. What is one step by man in relation to infinity? From this perspective, the Way is doomed to be nothing but an eternal beginning.

This feeling of not moving forward, of always being at the starting point, indicates to the traveller that the stations all come down to a single station that one must take the time to examine from every angle. The impression of advancing, of moving from one station to another, is engendered by an increase in “knowledge”, of a mastery of the Way, of the certainty that this effort generates.

This state should undoubtedly be related to the distinction which Ibn ‘Arabī makes between the makān (place) and the makāna (rank or position). While he is in the station, the sālik is in a place that he explores gradually. When he has come to know all the corners and nooks and crannies, he is transported, as a reward, to a “place” that is no longer a place (lā-makān) but a rank (makāna).

From this perspective, the lā-maqām would then be the unique moment when the sālik abandons the cycle, the eternal beginning again, to fall like a ripe fruit, against his own free will, into a new state, a state of perplexity. This would be the station of no-station.

The man who has been made perfect (al-mukammal) no longer has a harbour in which to drop his anchor. No station can contain him (can hold him) in existence (al-kawn).[23]

Like a fully inflated balloon, he is wrenched from the ground to rise up into the sky! This can be likened to a suitcase on a carousel at an airport. As long as no passenger comes to pick it up, it will go round and come past again several times waiting for the hand of its Owner to grab hold of it and take it off the carousel.

… from the first vertiginous fall of creation, from mirror to mirror, reducing in intensity until the final level from where one has to go back up again. The word “fall” should not be understood in a negative way, for the manifestation results from God’s desire to be known, to let Himself be known outside the Hidden Treasure (al-kanz al-makhfī). It is an explosion of joy, of light, the metaphysical big-bang. The immutable essences (a’yān thābita) do nothing other than follow the will of God and imitate Him by multiplying. They too, also wanted to see themselves, to make themselves known. They are affected by every decision of God.

Dar azal partov-e hosnat ze tajallī dam zad

‘eshq peydā shod o ātash be hame ‘ālam zad

In pre-eternity, the ray of your beauty decided to manifest itself

Love therefore appeared and set the whole world on fire. (Hāfiz)

The being which is in the first mirror sees God and sees itself in the second mirror (in imitation of God). It is thus the most recent manifestation of God, the one that is the closest to Him on the line of “descent”.

On the line of ascent, it is the last stage; the being has accumulated so much experience that it feels a very powerful energy (himmat) drawing it towards the Divine Eye. It has discarded created forms and strives with all its strength to return to the Source.

Rūmī says that human beings go from mineral to vegetable, and from vegetable to animal, before passing into the human state. And Ibn ‘Arabī adds that the human form is not adequate to define Man.[24]

On the line of ascent, as the sālik proceeds to climb the stages, he goes back up from mirror to mirror, reducing the number of mirrors that separate him from God. He measures his progress in terms of the spiritual energy (himmat) acquired at each stage that he passes through. He senses that his act of being (wujūd) is gaining in intensity, as Mollā Sadrā would say.

The station of no-station is the final moment when he emerges from the mirror to discover himself as a divine thought.

During the stages of the ascent, the sālik is constantly in motion. He moves progressively through the sequences of the film. He goes through them one by one, until THE END.

When he arrives at the station of no-station, he comes to a halt. The film is now projected before him. All the sequences are unfolded in front of him; he sees them all spread out together for him to review, still and lifeless. It was his own movement (of hayrat) that gave the impression of life, of moving images. In God there is no movement at all. Now he knows the sequence that is to come, and watches the frames of the film unwinding before his eyes. He has become a perfect master.

The film reveals that this destiny, this scenario, has existed since the beginning of time. God knew all the sequences of it. Having returned to God, he is allowed to see the world as God sees it. Thus, he will be able to say, like Hāfiz:

Sālhā del talab-e jām-e Jam az mā mī kard

Vānche khod dāsht ze bīgāne tamannā mī kard

For years on end, the heart asked us for the cup of Jamshid [cup of immortality]

In vain did it ask the stranger for what it already had.

This is what Abū al-Hasan al-Kharaqānī had in mind when he said: the Sufi is not created (al-sūfi ghayr makhlūq).[25]

He has de-created himself, as Chodkiewicz would say.[26] He has returned to the state of ‘ayn thābita, as an Akbarian would say. The Way leads us towards what we have been since the beginning of time.

No doubt it was after having entered into this state that ‘Ab-dulqādir al-Gilānī made his famous declaration: “This foot of mine here is on the neck of every saint of God” (qadamī hādhihi ‘alā raqabati kulli waliyy Allāh).[27]

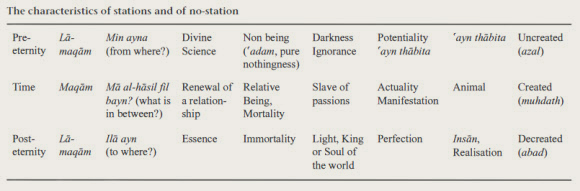

According to the question that was asked of Qūnawī: “From where (have you come?) and to where (are you going?), and what happens between the two?” (min ayn ilā ayn, fa mā al-hāsil fī l-bayn?),[28] he gave an impromptu answer giving the question a metaphysical significance: “(We have come) from (divine) knowledge (and we are going) towards the Essence. What happens in between is the renewal of a relationship that unites the two extremes and appears through both determinations.”

His reply can be illustrated by saying: we come from the origin of the manifestation of the stations and we return to no-station. The line that separates these two domains represents the real location of the Way, that which occurs between the two extremes, where the divine knowledge returns to the Essence, where the knowledge of men is re-united with (the ignorance of) the immutable essences.

In the ascent, the world was an illusion within an illusion (khayāl fī khayāl). In his perfection, the master sees the world undeniably as the manifestation of God (Haqq).

Innamā al-kawnu khayāl

Wa huwa haqqun fī l-haqīqā

Walladhī yafhamu hādhā

Hāza asrār al-tarīqa

The universe is an illusion

But it is true in reality

Whosoever understands this

Has grasped the secrets of the Way[29]

The secrets of the tariqa only allow themselves to be known by he who has travelled in both directions.

* * *

Sociological And Historical Degrees

For Plato, it is the thumos that is the origin of this spiritual aspiration, of this intuition that it is possible to attain a better state than the one in which one is currently, of this sorrow of the soul that longs to return to its source, that is to say to pass from the lower level where the stations are attained to the upper level where one leaves them behind.

This thumos gives Man the capacity for ambition, for righteous anger, and for indignation. Whereas reason on its own – as can be observed in the neutral stance of modern science – contents itself with saying things, with describing them, the thumos is the ana-gogic faculty that enables one to make a value judgment about things, and which aspires to go beyond them. It maintains what is otherwise known as social constraint, the fact that men have a desire to change a situation that is shocking and unacceptable. It manifests at an individual level, as in the example given by Plato of the person who, having succeeded in getting out of the cave, has no wish to return to it. But this example is equally valid for society since, according to Plato, the soul of the Republic is the algebraic sum of the individual souls of its members.

But this aspiration encounters stumbling blocks that can bring it to a halt, or lead it on by a longer route, or into an impasse. Man does not have the intuition of spiritual aspiration from the outset. The ambition of spiritual realisation is not always the conscious driving force, and it may be that he is unable to see beyond perfection of a material kind, or the attainment of some position or other in this world. In the latter case, this is somebody who has realised his relative perfection, even if he himself is unaware that that is its measure in relation to the criteria of the Way.

Herein lies the trap. But this aspiration can be interpreted as an obstacle to a divine name. For example, he who seeks power does not succeed in mastering the divine name the Powerful. Hence De Gaulle said: “I am the majesty of the French people!”. Someone who attains the degree of representation of a people can identify himself with it and speak in its name, well or ill, like Pharaoh saying: “I am your lord!”.

Every prophet fulfils his mission as a guide whilst at the same time seeking his own personal realisation. He has one side turned towards God (Haqq), and one side turned towards his people (Khalq). He is a saint in so far as he is turned towards his Lord. In the case of the Prophet of Islam, al-isrā’ (the Night-Journey), takes place when he is already preaching his message. On his return from his nocturnal journey, the Prophet returns with the Law (the prayer). It is the same for Moses (SA): the maqām al-qurba occurs for him after the ten years spent with Shu’ayb, according to Sulamī quoting Ibn ‘Ata, interpreting the verb ānastu nāran.[30]

On his return from the mountain, Moses returns with the tablets.

In both cases these are journeys that have a collective and communal effect. It can be concluded from this that the station of no-station is a prophetic station, whereas the qurbā, jam’, and jam’ al-jam’, are stations of sainthood.

This thumos is without doubt what in Sufism is called al-irāda, or active will. It is something that motivates the movement that is otherwise known as love. It is a desire to search for one’s origins, to go back to the source, to rise above the insouciance of the masses, to gain degrees, promotions.

Who is it that keeps this aspiration, this fire of God, burning? There is the ambiguity. In shi’ta qulta wa in shi’t qulta. One can say that it is man who aspires. One can say that it is God. What is essential is to understand that this irāda is the epiphany of the Divine Jealousy (ghayrah), for God Himself is implicated in the world, in order to defend His honour.[31] Wa mā qadaru Allaha haqq qadrihi… [32] “They have not measured (considered) God with His true measure… “

It is a question that has been summed up by a certain Sufi[33] in this ecstatic statement (shat-h): “The difference between my Lord and me is that I was the first to prostrate myself.”

In any event, it is the exhaustion of this irāda that will characterise and be the cause of the end of History according to Ibn ‘Arabī. The Hour will rise over men reduced to the animal state, satisfying their worldly desires. The divine call will hear no answering echo from such men. For Sufism, the driving force of history, its raison d’etre, is precisely the irāda. As the Tradition teaches, God will maintain the world as long as there is at least one man to say: Allah, Allah, Allah!

Sufi initiation consists in making sure of leaving the ship before it founders in the end of history. It is thus a doctrine of perfect salvation (soteriology).

Among the historians too, there is also this perception that history has a direction, a movement towards perfection. Toynbee sees challenge as being at the root of civilisation, without seeing that the challenge itself is underpinned by the idea of salvation.[34] All the efforts of the men of a particular civilisation are only the consequence of this desire to ensure their salvation, and of this spiritual aspiration, its fruits.

Every civilisation will be a manifestation of a divine form. The twenty-seven prophets of the Fusūs each symbolise a way of entering the station of no-station.

Today the phenomenon of globalisation can be regarded as the prefiguration of the realisation of a kind of total manifestation of all the names, as a kind of Insān kāmil in action. In the time of Ibn ‘Arabī too, they were attracted by this political tawhīd. Muslims were all seeking unity, but they could not see exactly of what it might consist. Some sought it in political unity, others in philosophy (the absolute Unity of Ibn Sab’īn). It was no coincidence that the dynasty which was in power at the time of Ibn ‘Arabī called itself Almohads (al-muwahhidūn: that is to say the ones that unify). But the perception of their leader Ibn Tūmert (who died in 524/1130) was, rather, of an artificial unity brought about by political force, which could only give rise to a monolithism.

That the station of no-station could concern an entire community, as a society – and not just an individual – is implicit in the Qur’anic verse[35] from which the expression originates. It is as though God wanted to say to them: “O people of Yathrib, you are not yet (as a community) ready for the station of no-station, for the complete manifestation will only come later. Return home. You are not the community that will unify the world, and in any event the world will not be unified in your time.”

This verse could also be interpreted thus, if one wants to round this off in a positive sense: “It is you who will serve as the model for future society. You will be the ideal city in the eyes of the men of the future.” Having attained the station of no-station, they are called upon to “return” (f-arji’ū) and to wait for the time to arrive when they will serve as guides to others. Because, as Ibn ‘Arabī emphasises, “the process is circular and eternal”.[36] For the perfection of perfection is to be in the station of no-station whilst at the same time being corporeally in this world. These “men of return” are the ones who keep the flame of active will burning.

This sociological or, if you like, socio-sophic interpretation of the verse is justified by the fact that the verse calls not upon an individual but a population, a human group consisting of the inhabitants of Yathrib (Medina). By extension, this can concern all of humankind.

In any event, the context of Yathrib allows Ibn ‘Arabī to draw the conclusion that this station of no-station is specific to the Muhammadan saints. He writes:

The highest category (of the saints) is that of no-station, and the reason for this is that the stations govern those that reside there.

Now there is no doubt that the highest category is the one that holds authority, not the one who is subject to authority… And that belongs to the Muhammadans alone, by a divine solicitude already given to them, as the Most-High has said: “As for those those whom we have already rewarded with splendour, they will be kept far from Gehenna.”[37] [38] The stations are therefore likened to a degree of Gehenna.

It is a station specific to Muhammadans for it is the station of praise (maqām al-mahmūd). Now, the standard of praise (liwā’ al-hamd) is in the hands of the Prophet whose three names Ahmad, Muhammad and Mahmūd derive from the same root.

The station of no-station is where the destiny of the individual will determine the destiny of the community, where destinies become a single destiny. Aeneas having become the symbol of Rome, lā-maqām signifies in relation to him that he is omni-present, in every Roman, in the sense that every Roman owes something to him, so that he has become a sort of psychological or even metaphysical universal.

Hence the insistence of all the commentators on the fact that the maqām al-mahmūd is characterised above all by the power of universal intercession that is recognised as belonging to the Prophet. Muhammad will intercede for all those who have recognised themselves in him and for all those (men and women) that he will recognise as his.

And so it is the case of Moses fighting with the strength of all the children of Israel who had died for him, because they were all potentially a Moses, individualities of Moses, the metaphysical universal.

Every society carries the “mark”, the imprint of its prophet, the mark that guides it in the right direction, or leads it astray. The guide may be faithfully imitated by his people. But he may also be vainly imitated by those whose faith is insincere: while Moses is on the mountain with the Lord, his people have a rendezvous with the golden calf.

In the work of Ibn ‘Arabī, the perspective of one world (globalisation), the sociological tawhīd, the universal manifestation in action, could not occur in History before occurring in spirit. If in its infrastructure the world is already one, it will only find stability in this unity if it is unified also in its superstructure.

The universal function of sealing belongs to the saints, and not to the Prophets.

The end of the world will come when the last man destined to pass through the station of no-station has succeeded in leaping into the divine absconditus. Those who have attained realisation, those who have already passed behind the curtain, are waiting for this saint of the final days.

When the last part of Perfect Man has crossed the Bridge, the world will collapse because it will no longer have any pillar to hold it up. And God will invert the hourglass of time again, ready for another beginning that will not be the same: “We turned (the earth) upside down… ” (Qur’an, XI: 82 or XV: 72). “On the Day when the earth is changed into other than the earth, and likewise the heavens, and they will be laid out before God the One, the Implacable” (Qur’an, XIV: 48).

Finally it should be noted that this sociological interpretation has already attracted many of the early Akbarians, especially those descended from the Kubrawiyya, up until the initiation of the Kabbalistic revolution (horūfiyya), by Fazlullāh Astarābādī.

It is also in a socio-sophic sense that Qaysarī interprets the verse: “Abraham was an Umma,”[39] by saying that Abraham contained all the communities that were to spring from him.[40] Likewise, Kāshānī made a connection between the substance of the prophecies and the dispositions of the peoples concerned by the teaching of the prophets.[41] There is a permanent connection between communities and their guides, but this connection is not one of necessity: Moses did not need his people. The higher does not need the lower.

Conclusion

All we have done is say things. We have not attained the station of no-station at all. Studying Sufism does not make one a Sufi. Spiritual experience cannot be summed up in words. Awhad al-Dīn Kermānī, who was a friend of Ibn ‘Arabī, uttered this quatrain:

The mysteries of the path cannot be solved by asking

nor by throwing away dignity and wealth.

Unless your heart and eyes shed blood for fifty years,

You will not be shown the way from words to states.[42]

If we must come to a conclusion, then the point that should be emphasised is that the stations all correspond to the degrees of acquisition of divine knowledge, from the lowest degree where the person knows nothing, but where he believes that he knows something, right up to the highest degree where the person has learnt much, but finally realises that he knows nothing. For this reason it is right to say, following Ibn ‘Arabī and those who followed him, that the lā-maqām is that of nescience, not knowing (maqām al-jahl, nā-dānī). But it is learned ignorance. To recognise one’s ignorance of God is the highest station that one can attain.[43]

For Ibn ‘Arabī, perfect knowledge of God is only possible through the affirmation of opposites as simultaneous truths. God is the First and the Last, the Apparent and the Hidden, and similarly the Knowing and the “Ignorant”.

Having returned to the state of ‘ayn thābita, in the “night” of the divine absconditus, it is evident that man is “unknown” as such; in the wujūd al-Haqq, the immutable essences are completely unknown, and even more so unknowing. This is no doubt what the Greek philosophers sensed when they claimed that God did not know individuals. But they did not suspect that this was only true from the perspective of the Essence envisaged as absolutely indeterminate.

A Qur’anic verse speaks of the creation and the resurrection as a moment that lasts no longer than the blinking of an eye.[44] When God opens his eye, He creates. When He closes it, He returns back to Himself. At every second, we make the return journey from God to God.

Thus we can understand why, in order to speak of the end, it was enough for us to speak of the beginning.

Translated from the French by Karen Holding.

This paper was originally presented at the twenty-first annual symposium of the Muhyiddin Ibn ‘Arabi Society, entitled “The Station of No Station”, held in Oxford, 15-16 May 2004. First published in Journal of the Ibn Arabi Society, Vol. XXXVII, 2005.

Annotations

[1] This paper was originally presented at the twenty-first annual symposium of the Muhyiddin Ibn ‘Arabi Society, entitled "The Station of No Station", held in Oxford, 15-16 May 2004.

[2] Ibn ‘Arabī, al-Futūhāt al-Makkiyya, Vol. I, p. 223: "or a person who having gathered together the stations then emerges from them into no-station like Abū Yazīd (al-Bistāmī) and his kind." I am using the Cairo edition of Futūhāt al-Makkiyya, 4 vols, 1 329 ah.

[3] Al-Tirmidhī, Kitāb khatm al-awliyā, ed. Othmān I. Yahyā (Beirut, 1965), p.143.

[4] Fusūs al-Hikam, Chapter 6 on Isaac. I am using the edition by Abū al-‘Alā’ ‘Afīfī (Beyrouth, 1946; repr. Tehran, n.d.).

[5] Eric Geoffroy, Initiation au soufisme (Fayard, Paris, 2003), p. 22.

[6] The Mawāqif and Mukhātabāt of Muhammad ibn Abdi’ l Jabbār al-Niffarī, A.J. Arberry edn (E.J.W. Gibb Memorial, London, 1932; repr. 1978).

[7] ‘Abd al-Rahmān Jāmī, Nafahāt al-Uns, Persian edn by Mahmud Abedī (Tehran, 1 370). The text of the letter to Kāshānīis on p. 490.

[8] Siyāha is the word used today in Arab countries to translate the word tourism.

[9] Qur’an, IX: 2.

[10] All the quotations of Rūmī are from his Kulliyyāt-e Shams (Tabrizī), also called Divān-e Kabīr, ed. Badī’uzzamān Foruzanfar (Tehran, 1336 AHsh./1 377 ah), 10vols.

[11] Qur’an, LIII: 9.

[12] Qur’an, XXXIX: 69.

[13] Ananda K. Coomaraswamy, The Transformation of Nature in Art (New York, 1934).

[14] Paul Valéry, Regards sur le monde actuel (Librairie Stock, Paris, 1933), pp. 53-4. Valéry was writing about politics.

[15] All the quotations of the great Iranian poet, Shamsuddin Hāfez Shīrāzī, are from his Dīvān, edited many times in Iran, the best edition being the one by Qazwīni and Qāsim-Ghanī. I am using a CD reproducing that edition.

[16] This story was related to me by my friend Daniel Abd al-Haqq Roussange, in Paris.

[17] Maybe this is what the Prophet meant when He said: "The best ones among you in Jahiliyya (before Islam) are the best ones in Islam."

[18] Nafahāt al-Uns, n.521, pp. 507-10.

[19] Futūhāt, Vol. III, p. 108.

[20] Qur’an, XX: 114.

[21] Qur’an, XVII: 78.

[22] Paper delivered at the University of Rabat, Morocco in October 2002 which appears as an article in JMIAS, XXXIII, pp. 1-21.

[23] Futūhāt, Vol.III, verse at the beginning of Chapter 351, p. 216. Alternative translation: his "non-maqām" holds him in the universe.

[24] See, for instance, Fusūs al-Hikam, Chapter on Noah, or Futūhāt, Vol. II, p. 499.

[25] See Kharaqānī, Paroles d’un Soufi, intro. and trans. by Christiane Tortel (Éditions du Seuil, Paris, 1998). See at the end of the book, my French translation of a short commentary of this saying by Najm al-Dīn Dāya in Arabic, from MS 760-5 (fos. 57a-61 b).

[26] Michel Chodkiewicz, Le Sceau des saints (Gallimard, Paris, 1986), p. 210.

[27] See Nafahāt al-Uns, p. 511.

[28] Anecdote told by Jāmī at the end of the note that he devotes to Qūnawī, n. 544, p. 554 of the new edn of the Nafahāt al-Uns.

[29] Fusūs al-Hikam, Chapter on Solomon.

[30] Qur’an, XX: 10. In this verse, Moses is thinking first of the interest of his family, and mentions personal guidance second.

[31] See Futūhāt, Vol. II, p. 10, where Ibn ‘Arabī talks of the jealousy (their jealousy is that of God) of the immutable essences in so far as they are immutable.

[32] Qur’an, VI: 91.

[33] Unfortunately for the moment I am unable to find a reference in my library for this well-known saying.

[34] I am using a French translation of the summary made by D.C. Somer- vell of Vols.I-VI of A Study of History by Arnold J. Toynbee, trans. into French by Elisabeth Julia (Gallimard, Paris, 1951), under the title L’Histoire, Un essai d’interprétation; see mainly Chapter 5.

[35] Qur’an, XXXIII: 13. The interpretation of this verse given by Ibn ‘Arabī is surprising. He relates this verse to the verse at XVII: 78-79, which is about the station of praise (maqām al-mahmūd) dedicated to the Prophet.

[36] Futūhāt, Vol. IV, p. 14, "li-kawn al-amr dawriyan".

[37] Qur’an, XXI: 101.

[38] Futūhāt, Vol.III, p. 106.

[39] Qur’an, XVI: 120.

[40] Dāwūd b. Muhammad al-Qaysarī, commenting on the Chapter on Moses, Vol. II, p. 402, in his Sharh Fusūs al-Hikam, 2 vols. (?Beyrouth, 1416).

[41] Fusūs al-Hikam, Chapter on Noah in which Kāshānī comments that the Word of Noah corrected (through tanzīh) the excesses brought about by the Word of Idris (tasbīh).

[42] Trans. by W.C. Chittickin Faith and Practice of Islam, Three Thirteenth- century Sufi Texts (SUNY, 1992), p. 70.

[43] Futūhāt, Vol.1, p. 108.

[44] Qur’an, LIV: 50. "Our commandment is but one (with its object), like the blink of an eye."